Search for articles, topics or more

browse by topics

Search for articles, topics or more

“Travel shows us otherness,” Thomas wrote, reflecting on the deep appeal that travel and tourism hold for people around the world. “We experience otherness when we come into contact with the unfamiliar – it is the feeling that things are different, alien.”

Travel and tourism broaden our horizons. They introduce us to new cultures, environments and experiences, providing a gateway to the unfamiliar that can lead us away from everyday concerns. Yet there is one respect in which tourism offers no sense of escape: its impact on the world’s ecosystems. According to research from the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO), tourism-related CO2 emissions grew by at least 60 per cent from 2005 to 2016, with transport-related CO2 causing 5 per cent of global emissions in 2016. This is the global picture, but specific tourism sites have also suffered ecologically: Thailand, for instance, was forced to close its Maya Bay beach in 2018 for three years to allow the beach’s ecology to recover after visitor numbers reached 5,000 per day. Faced with this level of environmental destruction, many have started to explore whether a form of more sustainable tourism might be possible.

.jpg) Desa Potato Head Bali ph. © All is Amazing Paulius Staniunas

Desa Potato Head Bali ph. © All is Amazing Paulius Staniunas

Desa Potato Head Bali ph. © All is Amazing Paulius Staniunas

Desa Potato Head Bali ph. © All is Amazing Paulius Staniunas

The UNWTO has begun to mobilise at an international level. In 2022, the organisation issued the Glasgow Declaration on Climate Action in Tourism, which commits its signatories from across the tourism industry to “halve emissions by 2030 and reach Net Zero as soon as possible before 2050”. This is no small challenge, and requires detailed, coordinated plans if countries are to improve the sustainability of their tourism offerings. A series of initiatives from around the world suggest that design may have a key role to play in the solution moving forward.

Take, for instance, Fogo Island off the coast of Newfoundland. The island has historically been economically dependent on a rapidly depleting fishing industry, and suffers from an ageing population now that the mainland offers greater opportunities for young people. Yet a lifeline for Fogo Island emerged in 2001, when Zita Cobb, a social entrepreneur born on the island, returned home after retiring from her work in Silicon Valley. Cobb quickly began implementing a series of cultural and economic initiatives across Fogo Island through her Shorefast charity, of which a central strand was to initiate a tourism industry that could provide a new economic outlet for the island.

FogoIsland Landscapes – ph Alex Fradkin

FogoIsland Landscapes – ph Alex Fradkin

Cobb was aware of the dangers of tourism to the island – acknowledging to Monocle magazine in 2013 that it’s “that butterfly wing thing; you end up damaging the very thing you’re trying to protect” – but grounded her ideas for the industry in a vision of tourism that would be culturally, environmentally and economically nourishing. Her Fogo Island Inn, for example, was designed by Newfoundland architect Todd Saunders to reflect the region’s history of vernacular timber structures that place sustainability at their core – to create a building, says Saunders, that “walks gently on the land”. Meanwhile, international designers including Elaine Fortin, Donna Wilson and Ineke Hans have designed furniture and textile pieces that can be produced on the island, and which make use of its history of craft and design – a means of reducing the need to import pieces from overseas, as well as providing economic opportunities for the islanders.

“It’s vital that [the inn] doesn’t take anything away from the island, but only adds to it”

Cobb told Monocle

Similar ideas have been adopted in Bali, where entrepreneur Ronald Akili’s Potato Head resort in Seminyak directly addresses the huge volume of waste brought to the island by tourism, which currently accounts for at least 13 per cent of all waste generated on Bali. In particular, the island’s ecology suffers from discarded single-use plastic, prompting Akili to ban the material from the resort as part of a concept he terms “regenerative hospitality”. “We think that is a concept that is essential in building a sustainable future within our industry,” he says. “Imagine if we can inspire a change of mindset where tourists, developers and operators are not only taking from the destination, but instead also helping regenerate it.”

Central to Akili’s aim is a programme that has invited designers such as Max Lamb, Faye Toogood and OMA to develop spaces, furniture and amenities for Potato Head that can be produced out of waste that is collected and processed on site, before being constructed by local craftspeople. These designs are either used on site or sold by the hotel. Lamb says that the “ambition is to achieve zero waste and ensure that nothing is leaving in the form of waste, but only leaving in the form of a converted product”.

“We think we can inspire the industry to operate with the idea of regenerating the destination,” says Akili. “When this changes, tourism can really be a force of good, promoting the exchange of ideas and creating solutions together.”

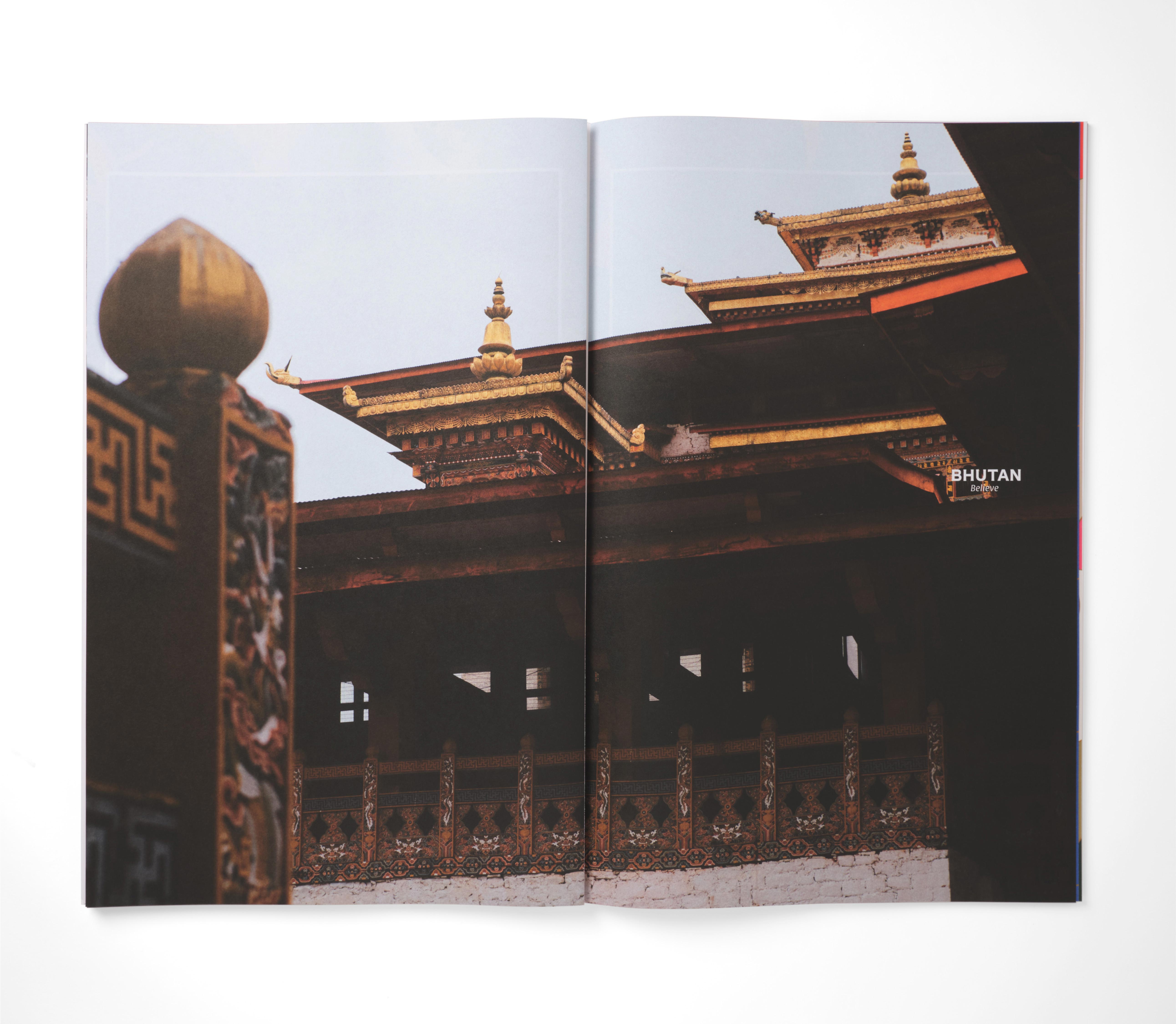

Bhutan

Bhutan

Translating these on-the-ground initiatives to a broader context is challenging, but guidance may be found in the example of Bhutan. In 2022, the Himalayan country worked with design agency MMBP & Associates to launch a new brand for the nation as well as its tourism industry. Pairing contemporary photography and graphic design, the brand details the country’s people, landscape, architecture and traditional culture, all focused around the word “Believe”. Chief among the brand’s aims is to explain to tourists Bhutan’s move to impose a $200 levy per person per day for tourists visiting the country – a fee that goes into Bhutan’s sustainable development fund, which supports its health, education and preservation programme. By highlighting the culture and nature that are central to Bhutan, the branding hopes to present this as a value that tourism can help pay to protect.

“If you go to Bhutan, you go there to trek, to experience the nature, the biomes,” said MMBP’s founder Julien Beaupré Ste-Marie to 032c magazine in 2022. “You don't go there to have a Michelin star meal and champagne.” In this sense, MMBP’s design work sought to explain a form of sustainable tourism that would be unfamiliar to many, but which Bhutan sees as essential to its future. “This tourism levy is a sustainable development fee, and the brand serves to really drive that point across,” Beaupré Ste-Marie told 032c. “The country is becoming more developed, but they don't want to compromise on their very long held values.” He added, “Part of our job was to explain to people that it's not expensive because it's ‘luxury’, but because it's a meaningful contribution to the country’s specific vision for development.”

In an age of climate collapse, these are just some of the routes that tourism may take as it seeks to become part of a more sustainable future. In this transition, design has a key role to play, helping to introduce new solutions as well as communicating the value of the ecosystems that the industry is seeking to protect. Travel may show us otherness, but design can help to highlight the shared values that can drive sustainable tourism in the years ahead.

Designers George Yabu and Glenn Pushelberg may operate studios in both Toronto and New York, but the pair are adamant that they do not differentiate between the two.

Caught between the Mediterranean blue and the warm Middle Eastern air is the island of Cyprus.

While travellers may come and go, however, it is the Amalfitans who call this place home with the Ponti's masterful touch.

Thanks for your registration.