Search for articles, topics or more

browse by topics

Search for articles, topics or more

When the first issue of Archivist launched in 2012, it was unlike any other fashion magazine. Instead of highlighting the new season’s trends, it showcased the history of garments, digging into the archives of fashion brands and reframing their contents with a contemporary lens. The hectic nature of fashion means the field rarely gets this pause for reflection. Instead, its output is quickly lost amid the continuous cycle of new seasons and trends. Archivist provided a refreshing take on an industry that has, at times, lacked analysis, scrutiny and appreciation.

But while Archivist tried to steer clear of trends, its launch nevertheless captured a certain mood – a trend for archives. In recent years, the use of and access to archives has started to form an increasingly prominent role in contemporary fashion and design culture.

Pieces based on archival material frequently feature in new furniture collections such as Molteni&C’s work with the Gio Ponti archive, while Swedish label Acne retails older collections under its Acne Archive brand. New digital ventures, such as Google’s We Wear Culture initiative, have also aimed to make certain archives more widely available.

So why are we suddenly seeing this interest in the archive, an entity that has historically been seen as a dusty repository of ideas from the past?

It seems one of the key reasons is a drive towards accessibility in design – an effort to make archival treasures available to the many, rather than the few experts traditionally granted access to these kinds of resources. We Wear Culture presents digitised collections from more than 180 museums, fashion institutions, schools and other archives from around the world, placing three millennia of fashion history at the casual browser’s fingertips. “It allows more democracy and more accessibility for the pieces that we have in the museum,” said Andrew Bolton, head curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute in New York and one of the partners in the project when it launched in 2017. The initiative now reaches millions of people globally.

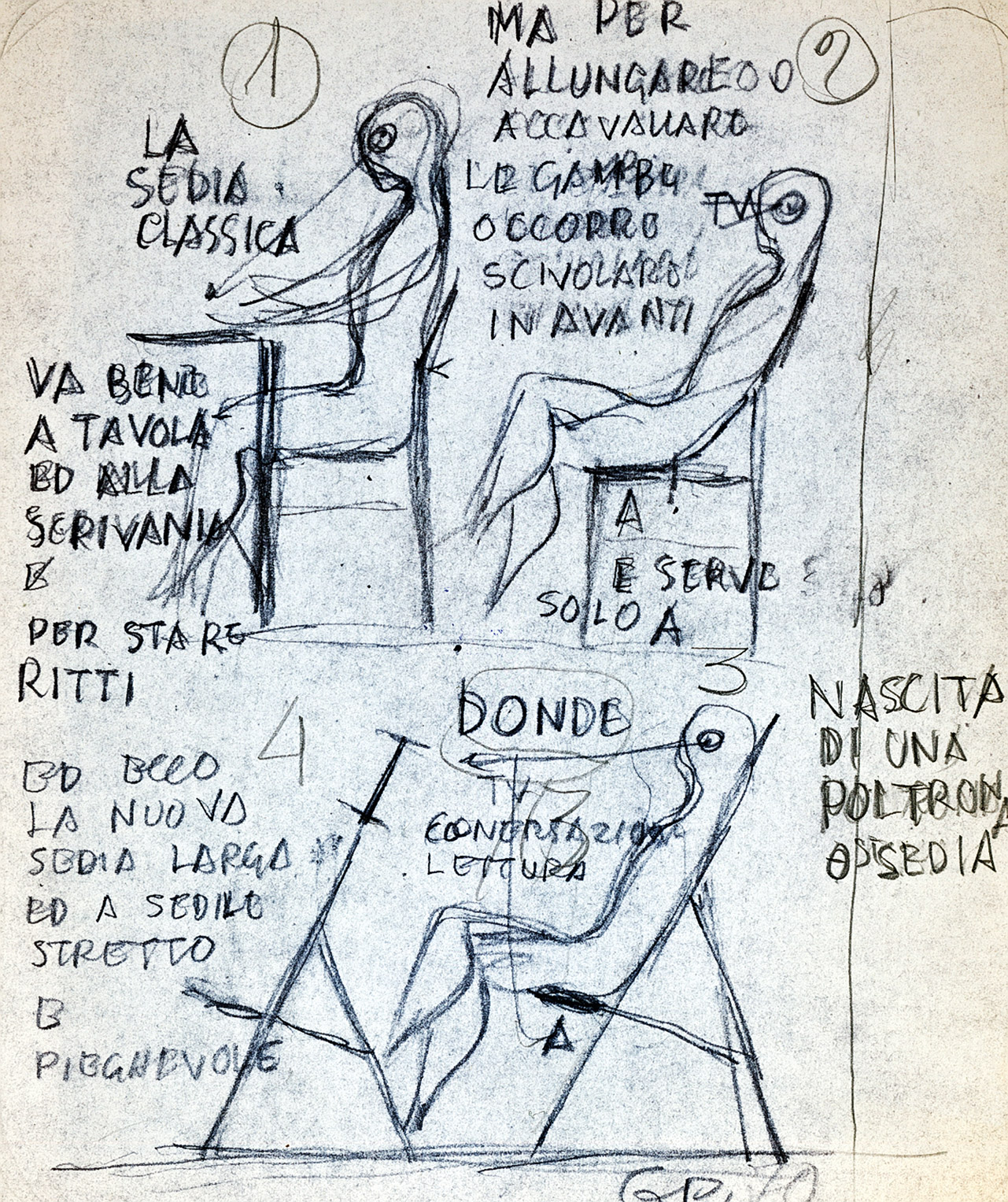

Gio Ponti sketch; courtesy Gio Ponti Archives

Gio Ponti sketch; courtesy Gio Ponti Archives

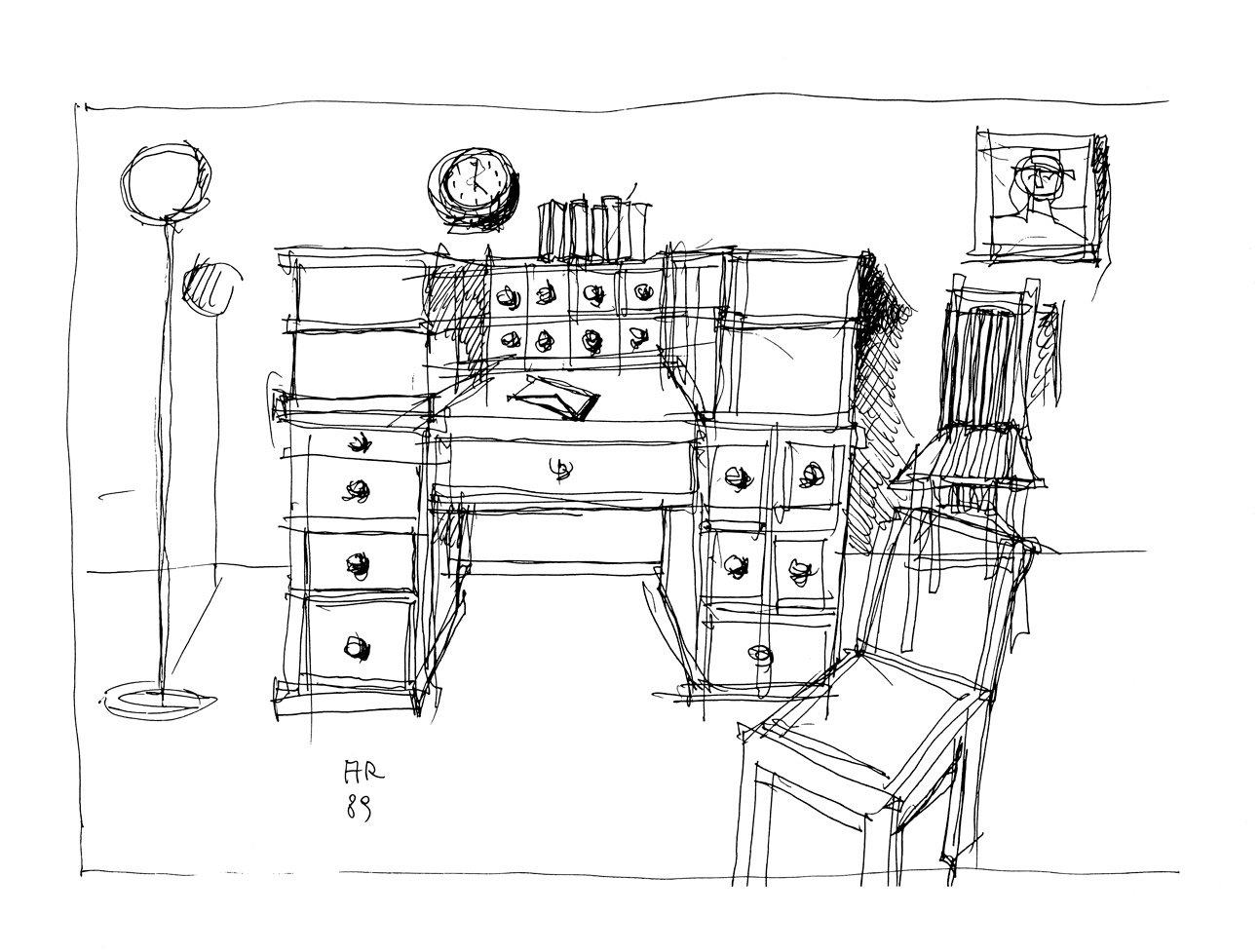

Aldo Rossi sketch; courtesy Fondazione Aldo Rossi

Aldo Rossi sketch; courtesy Fondazione Aldo Rossi

Last year, British publisher Bloomsbury launched Design Library, which provides a similar service for academic writing on design: an archive of more than 1,700 articles by leading scholars, spanning from 1500 BCE to the present day. Although it’s a paid-for service, it nevertheless makes available material that would otherwise be difficult to source from one place. In that sense, it capitalises on something that internet search engines have made us dependent on: instant access to all types of information without any time spent in libraries or actual archives. But physical archives have also enjoyed a revived interest, especially within design. In Italy, the design archive has become something of a phenomenon of late – a rare opening into a brand’s or person’s past.

Alessi Historical Archive

Alessi Historical Archive

The organisation Museimpresa assembles them under various different categories and its website guides you to weird and wonderful places across the country, often associated with places of manufacture. The Alessi archive at Museo Alessi in Crusinallo is one such example, right next to its manufacturing facility. Here a collection of prototypes, a complete backcatalogue of products and rare examples of print graphics encourage exploration of Alessi’s history.

In furniture design, archives have also become an important tool for the creation of new pieces. When Gio Ponti died in 1979, he left behind a rich collection of architecture and design drawings, housed in his old Milan studio on Via Dezza. In recent years, the designer Pierluigi Cerri has been browsing through the furniture archives with Ponti’s nephew, Salvatore Licitra, to select new pieces to resurrect for the Molteni&C collection. Furniture such as Ponti’s chair for the Montecatini building ,D.235.1, and the bookshelf he designed for his residence on Via Dezza ,D.375.1, has been revived for a new generation of consumers.

Meanwhile Molteni&C consolidated its own archive ahead of its 80th anniversary in 2015, creating a museum at its Giussano headquarters that brings some of the company’s history to life. “The Molteni archive was set up to keep together, and make easily accessible, all relevant company material, such as photography, catalogues, books and technical documentation that trace [the brand’s] history,” says Peter Hefti, its museum manager. “History for us is a guideline toward our future projects. We like to think that an archive is a living body, not only with the mission to act as custodian of the company’s history, but also to re-release relevant products that are valuable to our audience today.”

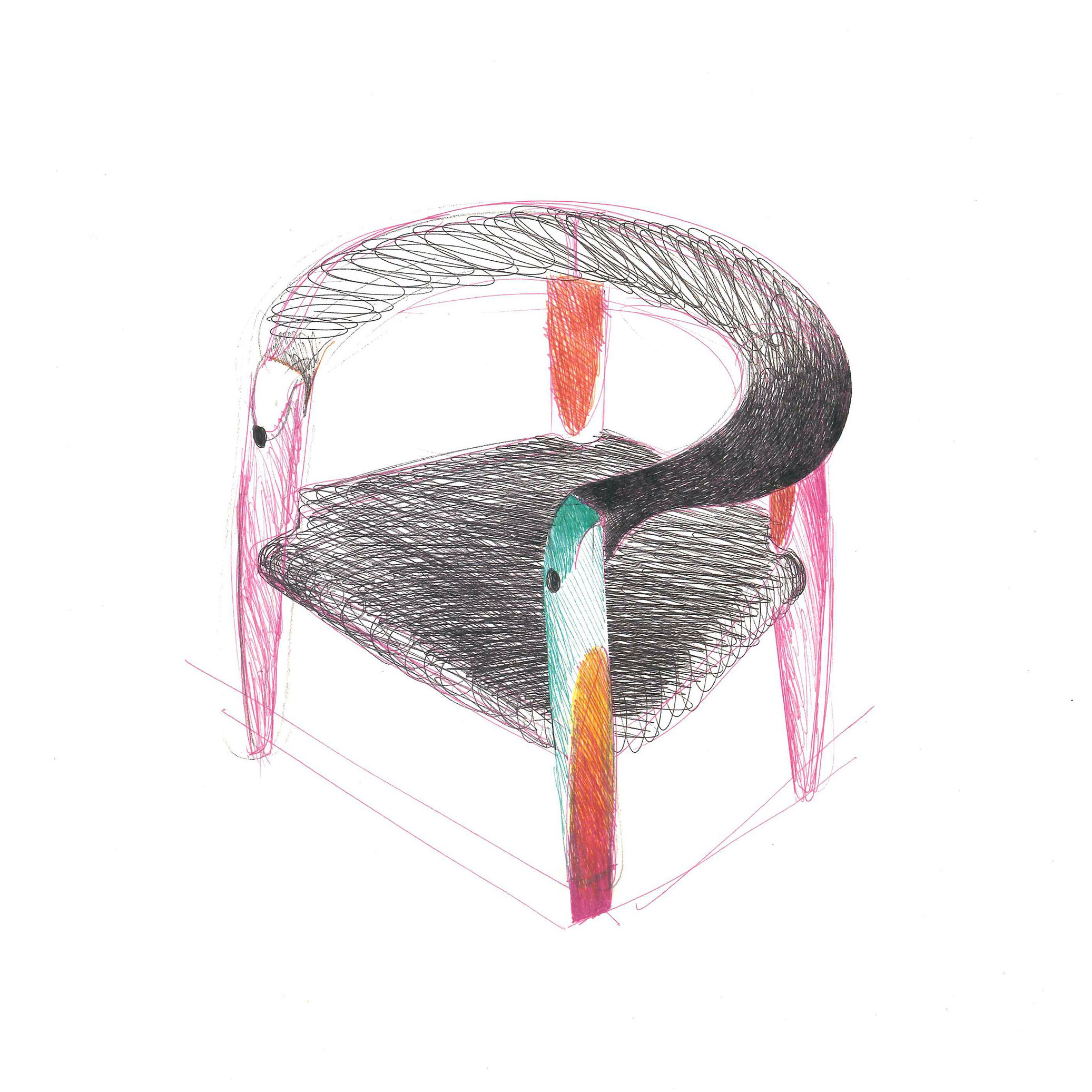

Miss, sketch by Tobia Scarpa. Molteni Historical Archive

Miss, sketch by Tobia Scarpa. Molteni Historical Archive

This decision has lead to new releases of older Molteni&C products by designers such as Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Yasuhiko Itoh and Werner Blaser. “These are examples of products that are seen as very modern nowadays, and they form an important part of our contemporary collection,” Hefti says. “It also reminds our customers of the long history of the company – many people are keen to be associated with a brand that has this history in its DNA.” Here, it seems that the archive is coming to serve a more active role in shaping contemporary culture, not just in defining the past.

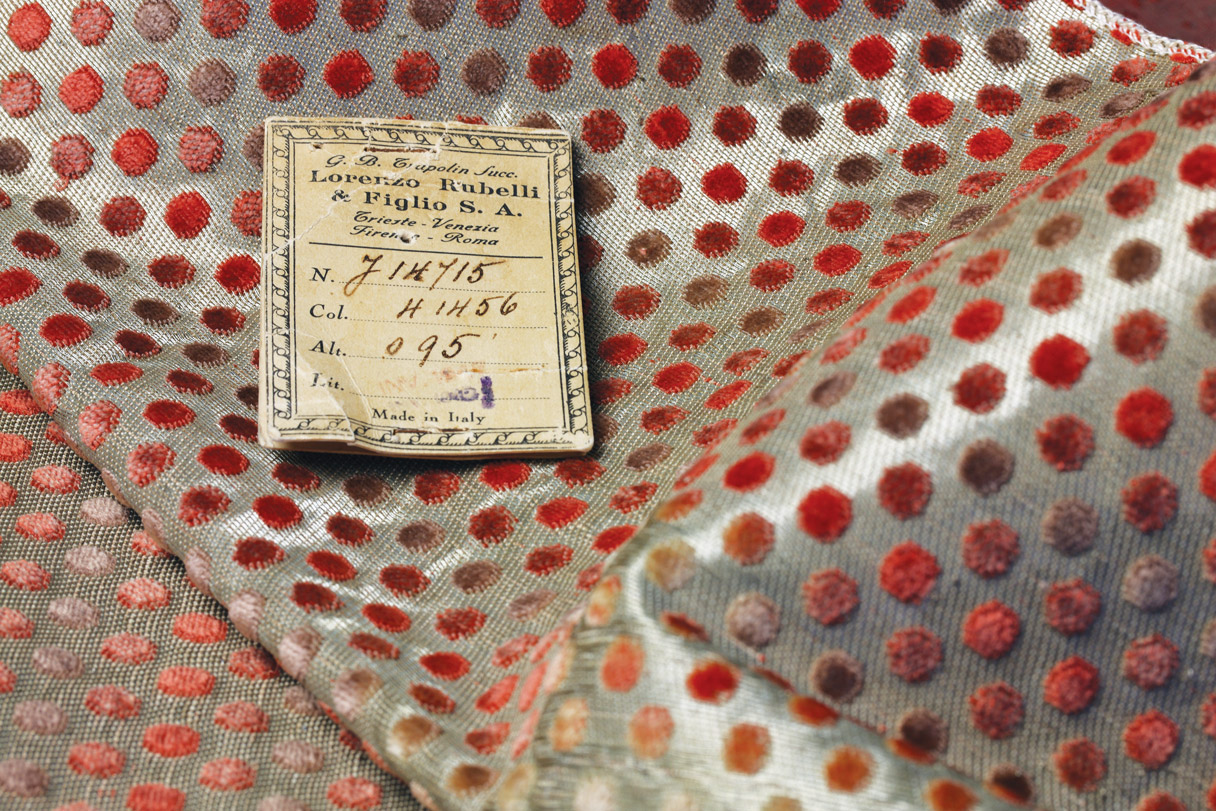

Punteggiato velvet by Gio Ponti, 1934; technical drawing; courtesy Rubelli Historical Archive

Punteggiato velvet by Gio Ponti, 1934; technical drawing; courtesy Rubelli Historical Archive

Observing things and remembering. This dual concept holds the key to understanding the ties between Aldo Rossi and design.

The story of M&C, the magazine produced by the Molteni Group, is a long one. When it was first distributed at the end of the 1980s, it was called simply Il Giornalone [“Large Newspaper”]

It was 1968, the year of great and definitive events that left their mark on consciences, cultures, populations, lifestyles, and consumer habits.

Thanks for your registration.